New CCSD grade reform gets mixed reactions

New policies garner mixed reactions from students, staff

Data from semester grades shows uneven results from grading reform.

March 22, 2022

Clark County School District has reformed its grading policies for this school year, which has resulted in several different opinions from students, parents and staff.

The school district’s new system promotes more equitable grading. At Silverado, the minimum grade students are able to receive is 50 percent. Late point deductions will now be eliminated, summative assignments such as tests and quizzes will count as 75 percent of a student’s grade, and students can redo most assignments.

“Grades should reflect a student’s understanding, not their ability to turn work in on time,” said photography teacher Rico Dunn. “So outside of courses in CTE that have standards tied to employability skills, factoring in deductions for lateness invalidates the grade because the grade is no longer based on the standards.”

Dunn, who is in favor of the grading reform, had already implemented most of the policies in his classes since before the pandemic, so he clearly supports these changes. Many students, including the Star staff in an editorial last fall, support these changes.

Others believe, however, that the district’s new grading reform will not be beneficial to students.

“I believe the new policies will benefit the minority and harm the majority,” Silverado Spanish teacher Joylyn Swenson said. “For students who need accommodations and who actually need the extra time or opportunity, no late points or unlimited retakes are a dream come true, and their stress level has dropped, helping them in overall academic improvement.”

But for many other students, teachers worry about bad study habits.

“However, the majority of students do not actually need these accommodations,” Swenson continued. “These policies (even unintentionally) facilitate laziness. There is a lot of accountability on the students now, but many students do not have the discipline to get work done when there is no real penalty until the end of the quarter.”

While teachers and students have different views on the new grading reform that was put in place this year, parents within the community have something to say as well.

“I feel it lowers the bar when we should be raising the bar to encourage our children to stay engaged in their studies,” Silverado parent Vicki Madsen said. “It makes it easier for kids to procrastinate and fall behind.”

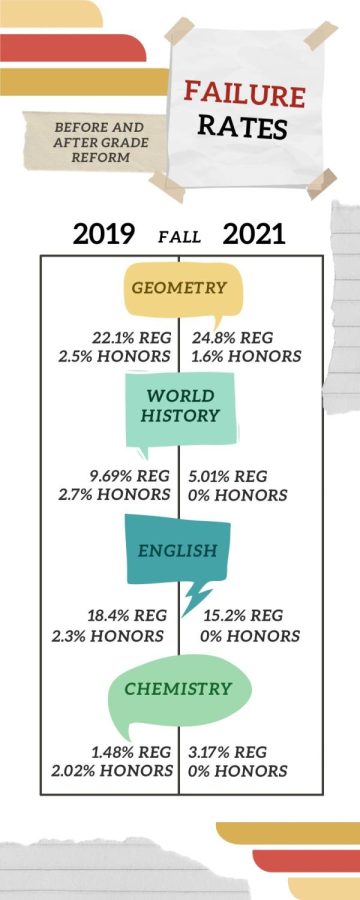

It is difficult to analyze how well the grading reform is working, but one thing to look at is how many students failed courses in the fall of 2019 before grading reform, and how many students failed courses this past fall in 2021 after grading reform. (The Star skipped looking at fall 2020 data since we were on distance learning.) We looked at the percentage of failing students, both regular and honors, in four core courses: geometry, English 10, chemistry and world history.

What we found is that a lower percentage of students failed history and English in fall 2021 after grading reform. In honors, the failure rate in both English and in world history honors changed from 1-2% to zero students failing.

But the trend we saw in these two humanities courses did not translate into STEM classes. While honors students in chemistry and geometry also did better after grade reform, regular students did not. While obviously students are still in the midst of a pandemic, and other factors can address failure rates, Principal Jaime Ditto confirms that this trend is seen throughout the district.

“Schools across the valley are seeing a decrease in the percentages of students failing classes,” Ditto said. “However, they are also seeing a decrease in the number of students earning an A. The traditional ‘bell curve’ in the grades is swollen in the middle, with less students on the bookends.”

One possible explanation for more students failing some courses is that last year during distance learning, students might not have fully understood subjects such as chemistry and geometry because they did not receive the hands-on learning experiences as they did the previous year. Humanities rely more on projects and writing, which students frequently do across all courses, but the content in math and science courses is highly specific, so if students do not know the material, they are more likely to fail a test.

It is also more critical in math and science to know how to solve a problem, whereas in English, students do know the basics of how to read and write when they get to high school, so it might be easier for them to get at least a D.

The new policies, while popular with students, remain controversial in CCSD and will no doubt receive more attention as we wrap up our first year with these reforms.